The employee-friendly glossary: 52 benefits terms that cause confusion, decoded

.webp)

Benefits jargon leaves many employees feeling lost, which can lead to missed opportunities and underused perks. This employee-friendly glossary breaks down 52 of the most commonly misunderstood terms in plain English, helping HR teams and employees alike navigate benefits with confidence. From deductibles to COBRA, this guide makes sure no one gets tripped up by confusing fine print.

Benefits are one of the most valuable parts of compensation, but also one of the most confusing. Research shows that 35% of employees don’t fully understand any of the benefits they enrolled in during open enrollment, highlighting a significant knowledge gap that drives confusion and missed opportunities. A big reason for that confusion is the jargon: acronyms, technical terms, and industry shorthand that make benefits feel like a foreign language.

That lack of understanding doesn’t just affect employees. It also costs employers, who lose billions each year in disengagement, poor plan choices, and underutilized benefits. For employers, clarity drives better utilization and higher satisfaction. For employees, it can literally mean thousands of dollars saved (or lost) each year.

Our hope with this guide is twofold: first, that employees gain a clear understanding of confusing benefits terms; and second, that HR leaders have a resource they can easily copy and paste from to provide plain-English explanations to their teams.

Benefits jargon can feel like navigating a foreign city: if you don’t understand the street signs, you’ll get lost, make wrong turns, and waste time. This glossary is designed to make sure no one has to feel that way about their benefits.

This guide breaks down 52 of the most misunderstood benefits terms. Each section explains:

- What it really means (in human terms, with an example if helpful)

- Why it’s confusing (and what it’s often mistaken for)

.webp)

Laws & Regulations

Affordable Care Act (ACA)

What it really means: The Affordable Care Act (ACA) is the landmark health reform law passed in 2010, often called “Obamacare.” For employers, it sets requirements for offering health insurance, like covering “essential health benefits” and ensuring affordability. For employees, it created marketplaces to shop for coverage and banned insurers from denying coverage due to pre-existing conditions.

Think of it as the “rules of the road.” Your health plan is the car you’re driving, and the ACA is the traffic laws that keep everyone safe.

Why it’s confusing: Many people use “ACA” as shorthand for health insurance itself, when in reality it’s the law that governs how insurance works.

COBRA

What it really means: COBRA, the Consolidated Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act, is a federal law that lets you keep your employer-sponsored health insurance after leaving a job (usually up to 18 months) if you pay the full premium. It’s the same coverage you had before, just now without your employer’s contribution.

Why it’s confusing: Many assume COBRA is a new or cheaper insurance plan, when in reality it’s just your old plan at full price.

Minimum Essential Coverage (MEC)

What it really means: MEC refers to the baseline level of coverage that satisfies ACA requirements. If you have MEC, you’ve met the legal standard for having health insurance. Think of it as passing the “inspection sticker” test for your car. It doesn’t guarantee luxury, but it means your coverage meets minimum safety standards.

Why it’s confusing: People assume MEC means “comprehensive” coverage, when in reality it’s just the legal floor.

Grandfathered Plan

What it really means: A health plan that existed before the ACA (March 23, 2010) and hasn’t made significant changes since then. These plans don’t have to follow some ACA rules.

Why it’s confusing: Employees often think “grandfathered” means better or more protective, when really it just means older and exempt from some updates.

Cost-Sharing Basics

Copay

What it really means: A fixed amount you pay when receiving care, like $20 for a doctor’s visit or $10 for a prescription. Copays are typically set by your insurance plan, meaning the amount doesn’t change based on which doctor you see (as long as they’re in-network) or how much the total bill is.

Why it’s confusing: Many assume copays are the same as coinsurance or deductible payments, but they’re separate. (More on those below.)

Deductible

What it really means: The amount you pay out of pocket each year before your insurance starts sharing the costs. For example, if your deductible is $1,500, you pay that first, then insurance begins to chip in. Some services, like doctor’s office visits or prescriptions with a set copay, don’t require you to meet your deductible first—you just pay the copay. But for larger expenses, like a surgery or hospital stay, you’ll pay the full cost until your deductible is met.

Why it’s confusing: People often mix up deductibles with copays (which are immediate) or out-of-pocket maximums (the most you’ll ever spend).

Coinsurance

What it really means: The percentage you pay for covered services after meeting your deductible. If you have 20% coinsurance, you pay 20% and insurance pays 80%.

Why it’s confusing: Employees sometimes mistake coinsurance for a flat fee like a copay, when in reality it only kicks in after your deductible has been met.

Out-of-Pocket Maximum

What it really means: The most you’ll ever pay for covered, in-network services in a plan year. Once you hit it, your insurance covers 100% of eligible costs for the rest of that year. For example, if your out-of-pocket maximum is $8,500, that’s the ceiling for deductibles, coinsurance, and copays combined, but only for covered services at in-network providers.

Why it’s confusing: People confuse it with annual maximums, which limit what insurance pays (not what you pay). It’s also misleading because not all costs count toward the out-of-pocket maximum. Out-of-network care, services not covered by your plan, balance billing (when providers charge above the insurer’s “reasonable” rate), and non-eligible expenses can all fall outside this cap. That’s how people can still face crippling medical debt, even with an out-of-pocket maximum in place.

Annual Maximum

What it really means: The most your insurance will pay in a year for certain types of coverage, usually dental or vision. For example, your dental plan might have a $1,500 annual maximum, like a gift card loaded with that amount. Once it’s gone, you’re responsible until the new plan year.

Why it’s confusing: Often mistaken for the out-of-pocket maximum, which refers to what you pay, not what the insurer pays.

Lifetime Maximum Benefit

What it really means: The maximum your insurance will pay over your lifetime for certain benefits. Though less common today (the ACA banned them for essential health benefits), you might still see it in dental or supplemental plans. Think of it as a lifetime credit limit.

Why it’s confusing: The phrase “lifetime” sounds like ongoing protection, so many assume it means unlimited or permanent coverage. In reality, it’s the opposite. It sets a ceiling on what the insurer will ever pay, and once you hit it, you’re responsible for all future costs.

Balance Billing

What it really means: When an out-of-network provider bills you for the difference between what they charge and what your insurance is willing to pay. For example, if a provider charges $1,000 for a procedure and your insurance determines the “reasonable” rate is $600, the provider may bill you for the remaining $400. It’s essentially the “balance” left on the bill after your insurer pays their portion.

Why it’s confusing: Many employees assume their out-of-pocket maximum protects them from unlimited costs, but balance billing usually doesn’t count toward that maximum. This is one of the main ways people end up with medical bills that feel overwhelming, even when they thought they were protected.

Eligibility & Coverage

Dependent Eligibility

What it really means: Rules that define who can be covered under your plan: usually spouses, children up to age 26 (as required by the ACA), and sometimes domestic partners if your employer includes them. Laws like the ACA set certain baselines, while each plan’s rules may add further restrictions. It’s like a guest list for a party: only certain people are allowed in, and the host (your employer/insurer) decides who makes the cut.

Why it’s confusing: People assume “dependent” means anyone financially dependent on them, but eligibility is defined strictly by the plan.

Dependent Verification

What it really means: The process of proving your dependents are eligible, often by providing documents like birth or marriage certificates.

Why it’s confusing: Employees often see it as unnecessary red tape, but dependent verification is typically required by employers, not insurers, as a safeguard. Employers are financially responsible for a big portion of plan costs, so they use verification to prevent ineligible dependents from being added. By ensuring only truly eligible dependents are covered, it helps control premiums and overall plan expenses.

Domestic Partner Coverage

What it really means: Coverage extended to an unmarried partner if your employer offers it. Usually, proof of shared residence or financial interdependence is required.

Why it’s confusing: Whether or not domestic partner coverage is available depends largely on the employer. There’s no federal mandate requiring it. However, some states and municipalities do require certain employers (especially public-sector ones) to offer it, which adds to the variation. This patchwork of rules means eligibility can look very different depending on where you live and who you work for.

Imputed Income

What it really means: The taxable value of benefits you receive, usually tied to domestic partner coverage. If your employer pays for your partner’s coverage and they’re not a tax-dependent, the IRS counts that as extra income. It’s like getting a free perk that still shows up on your W-2 as taxable value.

Why it’s confusing: Employees are often surprised by the extra tax hit, since the coverage itself feels like a benefit, not income.

Beneficiary (Life Insurance Beneficiary)

What it really means: The person (or people) who will receive the life insurance payout if you pass away. Your beneficiary doesn’t have to be someone on your insurance. It could be a sibling, parent, or trust.

Why it’s confusing: People confuse beneficiaries with dependents, assuming they’re automatically the same. In reality, you have to name beneficiaries when you enroll in life insurance (or when your employer provides it automatically). If you don’t, the payout could be delayed or default to your estate, which might not align with your wishes.

Portability (of insurance)

What it really means: The option to take certain insurance benefits (like life insurance) with you if you leave your job, often by converting them into an individual policy. Think of it as keeping your cell phone number when you switch carriers.

Why it’s confusing: Employees sometimes assume portability means the employer keeps paying for it, but you’re usually responsible for the full cost once you leave. It’s also not always clear how to exercise the option: typically, you notify your employer/HR when leaving, and then the insurance carrier takes over to set up billing and coverage directly with you. Missing those steps, or the often short deadlines, can cause employees to lose the option altogether.

Waiver of Coverage

What it really means: Choosing to decline your employer’s insurance, usually because you’re covered elsewhere. You often have to sign a form to document your choice.

Why it’s confusing: Some think “waiver” means they’re turning down coverage forever, when in fact it usually applies only to the current plan year.

Waiver of Premium

What it really means: A feature in some life insurance policies that lets you stop paying premiums if you become disabled, while the coverage stays in force. It’s like your subscription fee being paused automatically when you can’t work.

Why it’s confusing: The phrase makes it sound like anyone can simply waive their payments, but that’s not how most insurance works. In reality, waiver of premium only applies if you meet the policy’s definition of disability and are approved by the insurance company. Employees sometimes mistake it for waiving coverage altogether, instead of just waiving payments, or assume it’s a universal right across all plans when it’s really a specific built-in benefit.

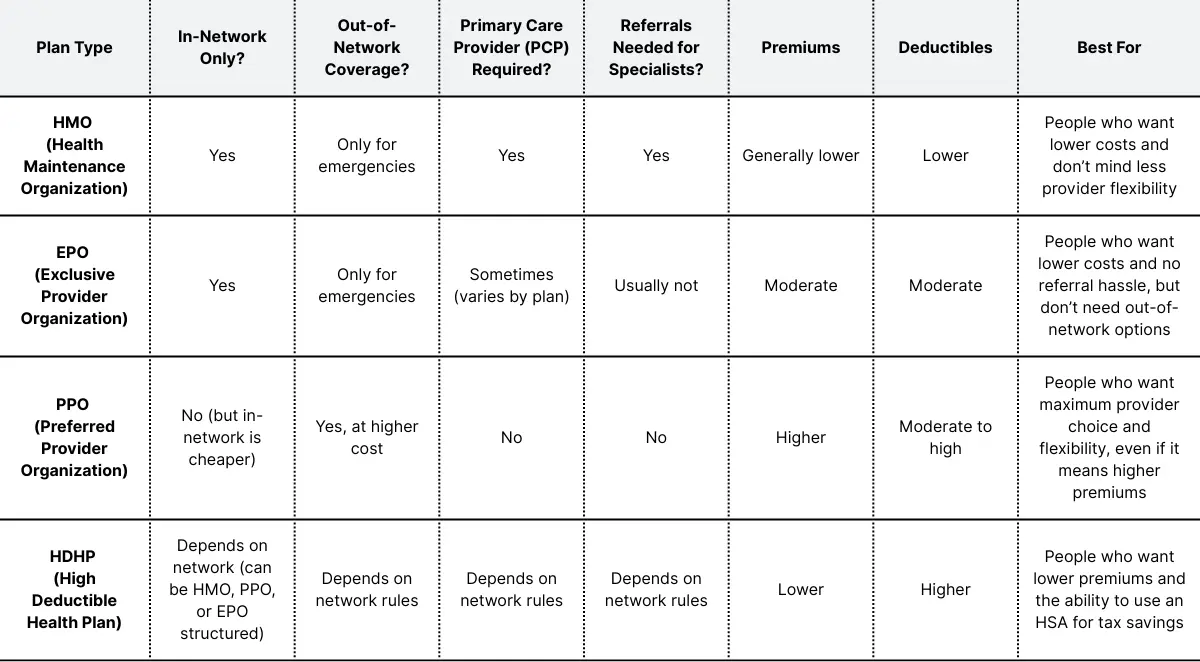

Plan Types

Health Maintenance Organization (HMO)

What it really means: A plan that requires you to stay within a network of doctors and usually get a referral from a primary care provider. Think of it like a members-only club like Costco or Sam’s Club. You get lower costs, but fewer choices.

Why it’s confusing: Many assume HMO means “cheap but low quality,” when in reality, the tradeoff is about rules: you need a primary care “gatekeeper,” referrals for specialists, and must stick with in-network providers. The care quality itself isn’t lower—it’s just managed more tightly.

Exclusive Provider Organization (EPO)

What it really means: An exclusive provider organization (EPO) is a plan that only covers care from in-network providers, with no referrals needed. It’s like an HMO without the gatekeeper.

Why it’s confusing: Employees often confuse EPOs with PPOs, not realizing out-of-network care isn’t covered at all.

Preferred Provider Organization (PPO)

What it really means: A flexible plan that lets you see both in-network and out-of-network providers, though in-network is cheaper.

Why it’s confusing: Employees often assume PPOs always mean better coverage because they offer more choice and don’t require referrals. But that flexibility comes with higher premiums, higher deductibles in some cases, and sometimes higher cost-sharing for services. In other words, you’re paying for freedom of choice, not necessarily for richer coverage or lower out-of-pocket costs.

Point of Service (POS) Plan

What it really means: A hybrid plan combining features of HMOs and PPOs. You choose a primary care provider and get referrals (like an HMO), but you can also go out-of-network for a higher cost (like a PPO). Think of it as a “choose your own adventure” plan.

Why it’s confusing: Employees often can’t tell how POS plans differ from PPOs since both allow out-of-network care. The key distinction is that POS plans usually require you to pick a primary care provider and get referrals for specialist visits, while PPOs let you see specialists directly. That referral requirement, plus differences in how out-of-network claims are reimbursed, makes POS plans a little more restrictive than PPOs, even though at first glance they seem the same.

High Deductible Health Plan (HDHP)

What it really means: A plan with a higher deductible but lower premiums, paired with eligibility for a Health Savings Account (HSA).

Why it’s confusing: People hear “high deductible” and assume it’s always a worse deal, without considering the tradeoff with HSAs and lower premiums.

In-Network

What it really means: Providers who have contracts with your insurance company to charge discounted rates. It’s like shopping at a store where you get member pricing.

Why it’s confusing: People assume “in-network” always means cheaper, but costs still depend on deductibles and coinsurance.

Out-of-Network

What it really means: Providers not contracted with your insurance. You’ll usually pay more because the insurer covers less (or sometimes nothing). It’s like shopping at a store that doesn’t accept your coupons.

Why it’s confusing: Employees sometimes think they’ll just pay a little more, not realizing out-of-network bills can be drastically higher.

Outpatient vs. Inpatient Care

What it really means: Outpatient care means you don’t stay overnight in the hospital (like a same-day surgery). Inpatient means you’re admitted and stay at least one night. It’s like the difference between dining out for one meal vs. checking into a hotel.

Why it’s confusing: Many assume outpatient means “minor” and inpatient means “serious,” but the distinction is about length of stay, not severity.

Accounts & Contributions

Flexible Spending Account (FSA)

What it really means: A flexible spending account (FSA) is an account where you can set aside pre-tax dollars to pay for eligible medical expenses. The savings come from taxes, so you’re using money before the IRS takes its cut. Think of it like buying things with a gift card loaded with tax-free money, which makes your paycheck stretch further for expenses you’d have anyway, like prescriptions or bandages.

Why it’s confusing: FSAs are “use it or lose it,” and many employees mistakenly assume unused funds roll over.

Dependent Care FSA

What it really means: A pre-tax account specifically for child care or dependent care expenses, like daycare or after-school programs. Think of it as a childcare savings account that lowers your taxable income.

Why it’s confusing: People mix it up with an FSA for medical expenses, but it can’t be used for healthcare.

Limited Purpose FSA

What it really means: A version of the FSA that can only be used for dental and vision expenses, often paired with an HSA. It’s like a gift card that only works at certain stores.

Why it’s confusing: Employees don’t always understand why it’s “limited” compared to a general FSA.

Health Savings Account (HSA)

What it really means: A savings account you can use for healthcare expenses if you’re enrolled in an HDHP. Contributions are pre-tax, the money grows tax-free, and withdrawals for eligible expenses aren’t taxed. It’s a “triple tax advantage” tool, almost like a 401(k) for healthcare.

Why it’s confusing: Employees often confuse HSAs with FSAs, not realizing HSAs roll over indefinitely and belong to you, even if you change jobs.

Pre-Tax Contribution

What it really means: Money taken from your paycheck before taxes are applied. Because your taxable income is lower, you end up paying less in taxes overall. It’s like your money skips the “tax toll booth” on its way to pay for benefits.

Why it’s confusing: People sometimes don’t realize their take-home pay looks smaller even though their taxable income is lower, which can make pre-tax contributions feel like they’re “losing money” when they’re actually saving.

Post-Tax Contribution

What it really means: Money deducted from your paycheck after taxes are taken out. Some benefits must be paid with post-tax dollars, like certain voluntary benefits (e.g., disability insurance, life insurance buy-up, or legal services plans). One upside is that if you ever receive a payout from these benefits (like a disability check), it usually won’t be taxed. It’s like buying something with money that’s already gone through the “tax toll booth.”

Why it’s confusing: Employees often don’t understand why some benefits use pre-tax dollars and others don’t. The difference comes down to IRS rules: health, dental, and vision insurance are typically pre-tax, while many supplemental or voluntary benefits are post-tax.

Disability & Life Insurance

Short-Term Disability (STD)

What it really means: Insurance that replaces part of your income for a short period (often 3–6 months) if you can’t work due to illness, injury, or childbirth. It’s like a financial bridge while you recover. In many cases, maternity leave pay is covered in part by STD benefits, so if you’re going on parental leave, you’ll need to coordinate with your STD insurance carrier (not just HR) to make sure the payments are set up.

Why it’s confusing: People often mistake STD as only for accidents, not realizing it commonly covers maternity leave too.

Long-Term Disability (LTD)

What it really means: Insurance that provides income replacement if you can’t work for an extended time, usually after short-term disability runs out. It’s like a long runway of financial support when recovery takes months or years.

Why it’s confusing: Employees often think LTD lasts forever, but it usually ends at a set age or after a defined number of years.

Evidence of Insurability (EOI)

What it really means: A health questionnaire (and sometimes a physical exam) you may need to complete to qualify for certain insurance amounts. It’s like proving you’re a safe driver before being allowed more coverage.

Why it’s confusing: People assume coverage is automatic, not realizing extra insurance often requires proof of health.

Guaranteed Issue

What it really means: A type of insurance coverage you can get without answering medical questions or providing health history, up to a set limit. It’s like being pre-approved for a credit card with a capped limit.

Why it’s confusing: Employees think “guaranteed issue” means unlimited coverage, but it’s usually only up to a specific dollar amount.

Buy-Up Option

What it really means: An option to purchase additional coverage beyond what’s provided at the default level. For example, your employer may provide life insurance equal to one year of salary, but you can “buy up” to more coverage, like upgrading from economy to premium economy on a flight.

Why it’s confusing: The phrase sounds optional and vague, so employees sometimes don’t realize it means paying extra for more protection.

Plan Documents & Processes

Explanation of Benefits (EOB)

What it really means: A statement from your insurer showing what was billed, what they covered, and what you owe. It’s like a receipt (not a bill) that explains the math.

Why it’s confusing: Many mistake an EOB for an actual bill and panic when they see large numbers.

Summary of Benefits and Coverage (SBC)

What it really means: A standardized document that outlines what a health plan covers and costs, meant for easy comparison across plans. You’ll usually see SBCs during open enrollment, but insurers are also required to provide them when you first become eligible for coverage, if you request one, or when there are major plan changes.

Why it’s confusing: Employees often find the SBC overwhelming because it still includes insurance jargon and cost scenarios that aren’t intuitive. If you’re skimming, focus first on:

- The coverage examples that show how much you’d actually pay in common situations, like having a baby or managing diabetes.

- The “Important Questions” section that has quick answers to things like deductible, out-of-pocket maximum, and network rules.

- The glossary link at the end (required in every SBC) for definitions of unfamiliar terms.

Summary Plan Description (SPD)

What it really means: A detailed document that explains how your benefits plan works, including eligibility, coverage, and how to file claims. It’s like the owner’s manual for your benefits.

Why it’s confusing: Many confuse it with the SBC, not realizing the SPD is longer, more detailed, and required by law.

Coordination of Benefits (COB)

What it really means: Rules for determining which insurance plan pays first if you’re covered under more than one plan (like through both you and your spouse). It’s like deciding who picks up the dinner tab when two people offer.

Why it’s confusing: Employees often expect both plans to pay in full, not realizing one is primary and one is secondary. You don’t get to choose which plan goes first. Insurance carriers follow set rules. For example, your own employer’s plan is usually primary for you, while your spouse’s plan is primary for them. For kids covered under both parents, there’s a “birthday rule”: the parent whose birthday comes first in the calendar year has the primary plan.

Prior Authorization

What it really means: Approval from your insurance company before certain procedures, prescriptions, or treatments are covered. It’s like getting a permission slip before going on a school trip.

Why it’s confusing: Employees often think prior authorization guarantees coverage, but it doesn’t. It only confirms the insurer agrees the service is medically necessary in advance. You could still be denied full coverage later if, for example, you go out-of-network, the service isn’t included in your plan, or the provider bills it differently. In other words, prior authorization is necessary for coverage, but not sufficient by itself.

Qualifying Life Event (QLE)

What it really means: A life change (like marriage, divorce, birth, or job loss) that allows you to change your benefits outside open enrollment. It’s like a hall pass that lets you make changes midyear.

Why it’s confusing: Employees sometimes think any life change qualifies, when only specific events count. Even when you do have a QLE, there are strict rules: you typically only have 30 days from the event (60 in some cases) to notify your employer and make changes. Miss that window, and you usually have to wait until the next open enrollment period.

Special Enrollment Period

What it really means: A window of time when you can sign up for or change coverage due to a QLE.

Why it’s confusing: People confuse it with open enrollment, not realizing it’s triggered only by specific events.

Open Enrollment

What it really means: The once-a-year period when you can sign up for or change benefits for the coming plan year. It’s like registration week for classes—miss it, and you’re locked in. During this window, you can:

- Enroll in or switch health, dental, and vision plans

- Add or drop dependents (unless a QLE happens later)

- Sign up for voluntary benefits like life or disability coverage

- Choose contribution amounts for accounts like FSAs or HSAs

Why it’s confusing: Employees often think they can make changes any time, not realizing options are limited outside this window. Open enrollment can also be overwhelming: employees may get a flood of information at once, face unfamiliar jargon, and feel pressured to make quick decisions. Add in that plan designs and premiums often change year to year, and it’s easy to see why many stick with “default” choices, even if they’re no longer the best fit.

Usual, Customary, and Reasonable (UCR) Charges

What it really means: The amount an insurer considers fair for a medical service, based on what providers in your area usually charge. If your provider charges more than the UCR, your insurer may only pay up to that amount.

Why it’s confusing: Employees often don’t understand why they owe more if a provider charges above UCR, assuming insurance should cover everything. This is where balance billing comes into play: providers can bill you for the difference between what they charge and what the insurer allows, and those extra costs typically don’t count toward your out-of-pocket maximum.

Miscellaneous & Voluntary Benefits

Ancillary Benefits

What it really means: Supplemental benefits that go beyond core medical insurance, such as dental, vision, life, and disability insurance. Employers often cover part of the cost for these benefits, making them feel like a middle ground between “core” coverage and fully optional perks. Think of them as the side dishes that round out your main meal.

Why it’s confusing: People sometimes lump ancillary benefits together with voluntary benefits since they’re both add-ons to medical coverage. The difference is that ancillary benefits are more common (like dental and vision) and often partially employer-paid, while voluntary benefits (like pet insurance or accident coverage) are usually 100% employee-paid.

Core Benefits

What it really means: The foundational benefits most employers offer, like medical, dental, and vision. Think of them as the base package of your compensation.

Why it’s confusing: Employees sometimes expect “core” to mean “all benefits,” but it usually excludes voluntary add-ons.

Voluntary Benefits

What it really means: Optional, employee-paid benefits like pet insurance, critical illness, or accident coverage. They’re like the à la carte items you can tack onto a meal.

Why it’s confusing: People sometimes think voluntary benefits are free, when in fact they’re often fully employee-paid.

How can technology help employees navigate their benefits?

Even with a glossary like this, benefits can still feel overwhelming. Employees juggle multiple plans, acronyms, and deadlines, often across different portals. In fact, only 44% of employees believe they have a good understanding of all their health and well-being benefits, according to industry research. That lack of clarity means benefits go underused—not because they aren’t valuable, but because employees don’t know where to find the information or how to take action.

That’s exactly the gap HQ for Employees, Nava’s free mobile app for employees, was designed to close. By centralizing benefits information, cutting out jargon, and providing year-round guidance and support, the app helps employees not only understand their options but also act on them with confidence.

HQ for Employees is designed to:

- Centralize all benefits info in one place so employees aren’t hunting across multiple logins and websites.

- Explain benefits in plain English: no jargon, just clear guidance.

- Provide personalized recommendations through our decision support tool so employees can see which benefits apply to their unique needs.

- Support employees year-round through AI and our team of benefits advocates, not just at open enrollment.

Think of it as putting the entire benefits package in your employees’ back pockets, with the clarity of a human benefits guide plus the convenience of an app.

When employees understand their benefits, they make smarter choices, save money, and appreciate their total compensation more. HQ for Employees was built to make that understanding easier than ever.

.webp)

.webp)